Negative Splitting Ultras

Over a decade ago, something started bothering me:

Why are even or slightly negative splits assumed to be optimal at the Marathon and below, yet it’s unheard of at 100 miles and longer?

The wisdom is usually along the lines of “you’ll get tired no matter what you do, so you should make good time early on” or “it’s just the way things are with night running, muscle breakdown, caloric intake, and everything else”.

For years I ran “traditional” smart ultra races where I finished much faster than the field, usually had an impressive kick, but still had significantly positive splits. In 2017, I decided to find out if true negative splits in ultrarunning were completely insane, or if they were just as powerful as at shorter distances but completely overlooked by everyone.

After 5 years and dozens of races, I want to convince you that not only is it the latter case, but that negative splits are actually more powerful than at shorter distances. Executing negative ultra splits has a way steeper learning curve than I expected, but also brings far more advantages than I ever imagined.

Virtually No Blow Ups - The longer the race, the more time there is for something to go wrong. Blowing up at mile 22 of a marathon means 4 miles of suffering. At a 50 mile, it could be 28 sucky miles. At 100 miles, it means a long long loooong day, plus night, plus maybe another day. When one thing goes wrong, it tends to make other things go wrong. Which makes even more things go wrong. Overheat? That will lead to stomach issues, which can lead to energy issues, which will mean hypothermia once the temperature drops. Going out slow enough to negative split means the risk of each individual problem goes down, but more importantly it means the chance of different problems interacting and compounding goes down much further. With more of a buffer, I found that any single issue that popped up was easy to mitigate before it caused anything else to cascade.

More Reliable Fast Races - There’s always a chance that an ultra will go south. But the better I get at negative splitting, the fewer blow ups I have, and the blow ups are less and less severe. In the past 12 months, I haven’t had a single bad race despite the most aggressive schedule I’ve ever attempted by a long shot. Many of them have been huge PRs, including a lot of “training” races that were much faster than previous “A” races.

Faster Recovery - This has been the biggest mind-blower for me. Typically at a 100, we hit mile 50 and start wondering how we can possibly hold on for 50 more miles. Even when we feel “good”, we’ve put the body through a lot and we spend 50 more miles pounding the damage deeper and deeper into our bodies. When I actually figured out how to hit mile 50 able to run the second half faster by absolute pace, something remarkable happened. Instead of 50 miles of light damage + 50 miles of deeper damage, I only came away with 50 miles of light damage from the second half. I noticed that reliably, I recover as if I’d only raced half of the distance. 100s feel like 50. 50s feel like 25.

Higher Training Density - Before, I would need to plan significant tapers and recovery periods around races, even ones I planned to train through. But because I started sustaining less damage at races, I’ve found I need a fraction of the recovery time. This means within a training cycle I can push average weekly miles much higher with the same amount of physiological load and risk, and I bounce back to “fully refreshed and excited to train” quicker and with less loss of fitness between training cycles. This has led to a big jump in the rate I’ve gained fitness year over year, and I’m quite frankly shocked where I’ve made it to now.

Better Experimentation - Normally in a race, it’s hard to try new things like different fuel, gear, or tactics. Not only is it risky, but it’s often hard to tease out their effects when masked by other issues popping up and affecting performance. With my races becoming more consistent, I’ve been able to try a lot more things, and actually single out their effects more easily than ever before. This has led to better and faster learnings, and a much more refined race plan than I assumed was achievable given all the variables in an ultra.

Less Pain Cave - I’ve always struggled with the grit I see in other ultrarunners. When the going gets tough, I often back off and struggle to push. But the more I negative split, the more I just feel straight up good late in a race.

Way More Fun - The hidden benefit of negative splitting is just how much fun it is. It’s hard to describe catching minutes a mile on the front runners in a race 80% in, and doing so without having to dig deep and suffer. I’ve really become addicted to it, and can’t imagine going back to the days of just hanging on to get to the finish line.

Fair enough. Let me get into more detail.

Actually executing a negative split is harder than it sounds, and the nuance is extremely important. My first attempts at negative splitting were extremely contrived - run way slower than I should for a race until halfway, then treat the second half like the actual race. The times were slower than if I had executed a normal race.

The key is that the naïve approach of just running slower is wrong, and there are two different ways to do it wrong.

Slow and Sloppy - This style was my first attempt. I slowed my pace down to have a faster second half, but treated the first half like a training run. While I didn’t overdo anything, I left a lot of time on the table.

Slow and Impatient - This style was my second attempt and more insidious. I suppressed the pace early on, yet stayed in “race” mode focusing heavily on taking care of myself, biding my time, and thinking about catching the competition. But in doing so, I jacked up my adrenaline, cortisol, and the rest of my endocrine system. I was essentially spinning my wheels, burning a lot of energy and stressing my system without actually covering a lot of ground. This led to strong early second halves because my muscles were fresh, with late fades as the rest of my body didn’t have enough to make it to the finish line.

The eureka moments came as I married these two. I had to be fully relaxed the first half in some kind of zen state of calm control, yet make optimal forward progress. I had to keep my excitement low while keeping my focus high. I had to direct all my energy toward both self-preservation and forward motion, while not using an ounce more energy than needed. Doing this, I found I could dial back my pace a minimal amount the first half while leaving enough to reliably speed up my absolute pace to the end.

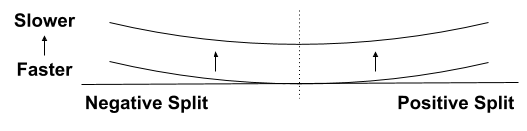

I will say, I’m not yet convinced even or negative splits are optimal for time. I would actually say most of my negative split races have been slower than optimal, but by design. For the sake of discussion, let’s say the optimal strategy is dead even splits. Then, for every finish time slower than that, there’s both a positive and negative strategy to achieve it. In the chart below, the line represents the same race effort with different pace strategies. In this case, we’re representing a maximum race effort.

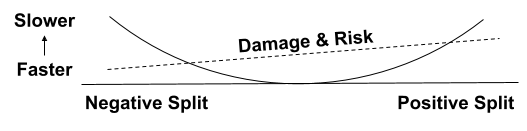

We don’t want to run a maximum race effort every time, so we can also shift the entire curve to be slower.

The slower the race, the lower the damage and faster the recovery. A negative split with the same damage & risk profile as a positive split will be much faster time wise. A negative split with the same time as a positive split will have much less damage and risk.

Putting all of these together, it becomes obvious that moving a positive split effort to the negative split effort with the same finish time will create less damage, have less risk, and bring faster recovery.

But there’s a less obvious and more important insight in this way of planning. All of this assumes we’re accurate estimating our abilities, and the kind of day we’ll have out on the course. But what if we’re wrong?

At the positive end of the curve, being wrong is catastrophic. The second half being slower means we’re already in the red, and we’ll only become more positive with more damage and cascading failures as we push to hold on. But with a negative split, we can dynamically adjust along the split and time dimensions as we please. We can stay on the same effort line and run a more even or positive split to maintain quick recovery. Or we can choose to push harder to a higher effort line to achieve the intended time at the cost of recovery.

In the worst case with negative splitting, things are not that bad. With positive splits, all options tend to be bad.

In practice, I’ve found a 3% negative split* to be a sweet spot of keeping the time fast while really getting all the benefits I described. For reference, my recent 13:20 100 mile with a 25 minute negative split hit this perfectly, and I raced a 50k the next weekend without issue.

* split = (second half - first half) / time

Zach Bitter - 11:19 100 Mile World Record - 2 minute negative split

Olivier Leblond - 171 Mile World 24 Hour in 2019 - 0.3% positive split

Possibly relevant, Zach asked me a week before his record if I was certain about my negative splitting theory I had been telling him about. The day before the World 24 Olivier mentioned to me that he was thinking about going out slower than he usually did and asked what I thought.

I have a huge interest in understanding this further, and getting data (even anecdata) beyond myself. I’d love to see others give this a try from different ability and experience levels to understand the extent that it works. If you’re interested in giving it a concerted attempt, I would love to hear from you, either in the comments below or by submitting a datapoint to a communal list of negative split attempts, which I’ve made publicly available. It would be great to see several others try this approach for a year or more to get over the initial learning curves.

Cumulative fitness - It’s possible most of these benefits are from hitting new fitness levels and would have happened without changing my pacing. Though I suspect it is symbiotic - higher fitness makes me more successful at negative splitting, and negative splitting helps me gain more cumulative fitness faster.

OFM & Vespa - I’ve experimented off and on with the high fat metabolism (lower carb generally with high carbs strategically timed) approach to ultra racing and believe it has played a significant part in my results. I’ve also done notable races on a traditional high carb diet (negative split 24 hour in 2018) so it’s in no way required. But it does seem to lend to more stable late race efforts for me, and when I added it to my negative splitting starting in 2019 my success rate and perceived recovery rate went through the roof.

Disclaimer - I’m currently on the Vespa Elite team as I have found great results with it, but I turn down the free product that comes with it and instead pay for it myself. I believe it’s helped me over the years, want to support it, and don’t want a financial conflict when talking about it. Take that for what it's worth.

Sleep, strength, and more - As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten better at the “in between” pieces like better sleep, strength training and general maintenance, etc. This has also had a positive effect on my overall performance.

If there’s interest in follow-up posts about these, let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Why are even or slightly negative splits assumed to be optimal at the Marathon and below, yet it’s unheard of at 100 miles and longer?

The wisdom is usually along the lines of “you’ll get tired no matter what you do, so you should make good time early on” or “it’s just the way things are with night running, muscle breakdown, caloric intake, and everything else”.

For years I ran “traditional” smart ultra races where I finished much faster than the field, usually had an impressive kick, but still had significantly positive splits. In 2017, I decided to find out if true negative splits in ultrarunning were completely insane, or if they were just as powerful as at shorter distances but completely overlooked by everyone.

After 5 years and dozens of races, I want to convince you that not only is it the latter case, but that negative splits are actually more powerful than at shorter distances. Executing negative ultra splits has a way steeper learning curve than I expected, but also brings far more advantages than I ever imagined.

The Outcomes

What have I gotten from frequently negative splitting at 50k to 150+ miles?Virtually No Blow Ups - The longer the race, the more time there is for something to go wrong. Blowing up at mile 22 of a marathon means 4 miles of suffering. At a 50 mile, it could be 28 sucky miles. At 100 miles, it means a long long loooong day, plus night, plus maybe another day. When one thing goes wrong, it tends to make other things go wrong. Which makes even more things go wrong. Overheat? That will lead to stomach issues, which can lead to energy issues, which will mean hypothermia once the temperature drops. Going out slow enough to negative split means the risk of each individual problem goes down, but more importantly it means the chance of different problems interacting and compounding goes down much further. With more of a buffer, I found that any single issue that popped up was easy to mitigate before it caused anything else to cascade.

More Reliable Fast Races - There’s always a chance that an ultra will go south. But the better I get at negative splitting, the fewer blow ups I have, and the blow ups are less and less severe. In the past 12 months, I haven’t had a single bad race despite the most aggressive schedule I’ve ever attempted by a long shot. Many of them have been huge PRs, including a lot of “training” races that were much faster than previous “A” races.

Faster Recovery - This has been the biggest mind-blower for me. Typically at a 100, we hit mile 50 and start wondering how we can possibly hold on for 50 more miles. Even when we feel “good”, we’ve put the body through a lot and we spend 50 more miles pounding the damage deeper and deeper into our bodies. When I actually figured out how to hit mile 50 able to run the second half faster by absolute pace, something remarkable happened. Instead of 50 miles of light damage + 50 miles of deeper damage, I only came away with 50 miles of light damage from the second half. I noticed that reliably, I recover as if I’d only raced half of the distance. 100s feel like 50. 50s feel like 25.

Higher Training Density - Before, I would need to plan significant tapers and recovery periods around races, even ones I planned to train through. But because I started sustaining less damage at races, I’ve found I need a fraction of the recovery time. This means within a training cycle I can push average weekly miles much higher with the same amount of physiological load and risk, and I bounce back to “fully refreshed and excited to train” quicker and with less loss of fitness between training cycles. This has led to a big jump in the rate I’ve gained fitness year over year, and I’m quite frankly shocked where I’ve made it to now.

Better Experimentation - Normally in a race, it’s hard to try new things like different fuel, gear, or tactics. Not only is it risky, but it’s often hard to tease out their effects when masked by other issues popping up and affecting performance. With my races becoming more consistent, I’ve been able to try a lot more things, and actually single out their effects more easily than ever before. This has led to better and faster learnings, and a much more refined race plan than I assumed was achievable given all the variables in an ultra.

Less Pain Cave - I’ve always struggled with the grit I see in other ultrarunners. When the going gets tough, I often back off and struggle to push. But the more I negative split, the more I just feel straight up good late in a race.

Way More Fun - The hidden benefit of negative splitting is just how much fun it is. It’s hard to describe catching minutes a mile on the front runners in a race 80% in, and doing so without having to dig deep and suffer. I’ve really become addicted to it, and can’t imagine going back to the days of just hanging on to get to the finish line.

Too Good to be True

“But Nick, that all sounds too good to be true. I don’t believe you.”Fair enough. Let me get into more detail.

Actually executing a negative split is harder than it sounds, and the nuance is extremely important. My first attempts at negative splitting were extremely contrived - run way slower than I should for a race until halfway, then treat the second half like the actual race. The times were slower than if I had executed a normal race.

The key is that the naïve approach of just running slower is wrong, and there are two different ways to do it wrong.

Slow and Sloppy - This style was my first attempt. I slowed my pace down to have a faster second half, but treated the first half like a training run. While I didn’t overdo anything, I left a lot of time on the table.

Slow and Impatient - This style was my second attempt and more insidious. I suppressed the pace early on, yet stayed in “race” mode focusing heavily on taking care of myself, biding my time, and thinking about catching the competition. But in doing so, I jacked up my adrenaline, cortisol, and the rest of my endocrine system. I was essentially spinning my wheels, burning a lot of energy and stressing my system without actually covering a lot of ground. This led to strong early second halves because my muscles were fresh, with late fades as the rest of my body didn’t have enough to make it to the finish line.

The eureka moments came as I married these two. I had to be fully relaxed the first half in some kind of zen state of calm control, yet make optimal forward progress. I had to keep my excitement low while keeping my focus high. I had to direct all my energy toward both self-preservation and forward motion, while not using an ounce more energy than needed. Doing this, I found I could dial back my pace a minimal amount the first half while leaving enough to reliably speed up my absolute pace to the end.

Dials, not Switches

The next key is to understand that none of this is binary. It’s a sliding scale of tradeoffs and probabilities. The more I understood them the more I could choose the outcome that best fit into my goals.I will say, I’m not yet convinced even or negative splits are optimal for time. I would actually say most of my negative split races have been slower than optimal, but by design. For the sake of discussion, let’s say the optimal strategy is dead even splits. Then, for every finish time slower than that, there’s both a positive and negative strategy to achieve it. In the chart below, the line represents the same race effort with different pace strategies. In this case, we’re representing a maximum race effort.

We don’t want to run a maximum race effort every time, so we can also shift the entire curve to be slower.

The slower the race, the lower the damage and faster the recovery. A negative split with the same damage & risk profile as a positive split will be much faster time wise. A negative split with the same time as a positive split will have much less damage and risk.

Putting all of these together, it becomes obvious that moving a positive split effort to the negative split effort with the same finish time will create less damage, have less risk, and bring faster recovery.

But there’s a less obvious and more important insight in this way of planning. All of this assumes we’re accurate estimating our abilities, and the kind of day we’ll have out on the course. But what if we’re wrong?

At the positive end of the curve, being wrong is catastrophic. The second half being slower means we’re already in the red, and we’ll only become more positive with more damage and cascading failures as we push to hold on. But with a negative split, we can dynamically adjust along the split and time dimensions as we please. We can stay on the same effort line and run a more even or positive split to maintain quick recovery. Or we can choose to push harder to a higher effort line to achieve the intended time at the cost of recovery.

In the worst case with negative splitting, things are not that bad. With positive splits, all options tend to be bad.

In practice, I’ve found a 3% negative split* to be a sweet spot of keeping the time fast while really getting all the benefits I described. For reference, my recent 13:20 100 mile with a 25 minute negative split hit this perfectly, and I raced a 50k the next weekend without issue.

* split = (second half - first half) / time

Experiment of 1

All of this being said, this entire theory hinges on a 5 year experiment of one (me), and there are plenty of confounding factors affecting the results I experienced. I’ve tried to find other accounts of even-ish splits at 100+ miles, and have only found two that I can verify. Though I’ll say the list only convinces me further that this can work:Zach Bitter - 11:19 100 Mile World Record - 2 minute negative split

Olivier Leblond - 171 Mile World 24 Hour in 2019 - 0.3% positive split

Possibly relevant, Zach asked me a week before his record if I was certain about my negative splitting theory I had been telling him about. The day before the World 24 Olivier mentioned to me that he was thinking about going out slower than he usually did and asked what I thought.

I have a huge interest in understanding this further, and getting data (even anecdata) beyond myself. I’d love to see others give this a try from different ability and experience levels to understand the extent that it works. If you’re interested in giving it a concerted attempt, I would love to hear from you, either in the comments below or by submitting a datapoint to a communal list of negative split attempts, which I’ve made publicly available. It would be great to see several others try this approach for a year or more to get over the initial learning curves.

Other Factors

On the devil’s advocate side, I don’t want to dismiss some confounding factors at play in my own journey which are worth mentioning:Cumulative fitness - It’s possible most of these benefits are from hitting new fitness levels and would have happened without changing my pacing. Though I suspect it is symbiotic - higher fitness makes me more successful at negative splitting, and negative splitting helps me gain more cumulative fitness faster.

OFM & Vespa - I’ve experimented off and on with the high fat metabolism (lower carb generally with high carbs strategically timed) approach to ultra racing and believe it has played a significant part in my results. I’ve also done notable races on a traditional high carb diet (negative split 24 hour in 2018) so it’s in no way required. But it does seem to lend to more stable late race efforts for me, and when I added it to my negative splitting starting in 2019 my success rate and perceived recovery rate went through the roof.

Disclaimer - I’m currently on the Vespa Elite team as I have found great results with it, but I turn down the free product that comes with it and instead pay for it myself. I believe it’s helped me over the years, want to support it, and don’t want a financial conflict when talking about it. Take that for what it's worth.

Sleep, strength, and more - As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten better at the “in between” pieces like better sleep, strength training and general maintenance, etc. This has also had a positive effect on my overall performance.

Even More

I’m only lightly touching on the learnings I’ve had over the last 5 years. I’ve developed frameworks around negative splitting strategies, how I estimate what time to shoot for, and how to actually align my perceived effort with all of this.If there’s interest in follow-up posts about these, let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Subscribe to get email updates when I release more posts.

Great article Nic. I would be interested in trying this as a 50 year old plant based runner.

ReplyDeleteI think this is absolutely fascinating. I've been watching your progress over the past year-and-change and often wondered why you seem to be so comfortable and reliable when it comes to negative splits.

ReplyDeleteMy ability probably isn't worth noting, but when my knee heals, I'll see if I can pull any information together for this project. Thanks for all your work on this, and your willingness to put it out there, Nick.

Cheers,

Brian

Really cool and insightful. I do think it gets tricky when we consider course profiles, as many ultras are across varying terrain. My most recent ultra had about 60% of the climbing in the latter half of the race, so I expected to positive split, and did so, but only minimally. I believe I managed effort well and didn’t really feel like I went to the well until the final 2 miles. I recovered much quicker than any of my other races (about 3 days). I’m anxious to experiment with your approach.

ReplyDeleteNic, this is VERY intriguing. I would likely more fall into the novice category but would definitely be interested in testing your theory. I think my greatest struggle would be on the assessing my own abilities part. Definitely interested in more detail and follow up posts!!!

ReplyDeleteHey Nick, Nickademus here, what a great post and great information you've put out there. Seeing you grow so incredibly much the last five years, wow, you've really come along so far with your relationship with the sport. Thank you for putting this information out here. I have two questions/ curiosities with this: 1) how do you integrate negative split running into a loop or unidirectional mountain course (Wasatch, Hardrock etc..)? 2) having worked on personal mental health issues (such as high anxiety) the past four years myself, I found so much of my positive split running was and is still based in "keeping up with the front runners." Do you feel a portion of your growth/ ability to run negative splits has come from a more stable sense of self/ self-confidence as you've aged?

ReplyDeleteFor #1, I try to difficulty adjust the pace for terrain, heat, night, etc but then mostly apply the same exact principles. And for things like heat and night I first try to mitigate them with race strategy to minimize the slowdowns.

DeleteFor #2 it’s something I figured out well before all of the rest and has helped me never really get caught up in the front pack, and really do the opposite most times. At the start of the race I let the lead pack blow by me, then the runners in the second pack, then all the hopefuls trickling behind them. The whole time I tell myself “I’ll see you later, and I’ll see you later, and I’ll definitely see YOU later” as I imagine the various blowups and slowdowns the other runners are setting themselves up to have. It may not feel satisfying at first, but once you are 30-40% into the race and those runners start coming back to you, it starts reinforcing the principle. Then it just keeps continuing the whole race. After doing that for a race or two, it becomes way more satisfying than going out with the lead pack and risking being one of those casualties.

Great article. These are concepts I’ve experimented with for 20 years as well. I’ll have some data for you when I return from a business trip. Excited to share the journey with you.

DeleteCongrats on your 24 hour US record. It was awesome to see you on the track clicking away lap after lap at the same pace and looking strong. I'd like to see a follow up post on the point in the "Even more" section especially in the context of mountain ultras. Recover well and savor the well earned record.

ReplyDeleteYes. One of the unfortunate effects of training for this effort is It's taken me months to find the time for each post. Hoping to get more out sooner now that I will have a bit more time!

DeleteThank you for sharing this. I've ran many marathons before and know first hard the benefits of negative splits. I'm about to run my very first 50 miler and your article was very informative. Congratulations on your achievements.

ReplyDelete